Nagaland, home to 17 major tribes and numerous sub-tribes, each with its distinct language, customs, and traditions, is also among the states consistently struggling with deep-rooted educational challenges and low learning outcomes. A large section of its population belongs to historically marginalised communities and Scheduled Tribes, making exclusion from quality education a generational hurdle.

Beyond the layers of marginalisation and poverty, the state’s formidable terrain poses yet another challenge for children who aspire for the opportunities schools can provide. Hilly villages and scattered settlements, along with floods and landslides, add complexity to education. No matter how much effort is invested in building a more equitable and responsive education system, it will not matter if students have to travel from the hills to the valleys just to be present in a classroom.

According to the PARAKH Rashtriya Sarvekshan Report 2024, students in Grade 3 scored 3% below the national average (60%) in mathematics and 1% below in language(64%) . As children progress through grades, dropout rates rise sharply, with many leaving school to migrate with their families, to engage in labour, or due to instability and conflict. By Grade 6, students in rural schools scored 8% below the national average in mathematics and 1% below in language, reflecting a widening gap in foundational learning as they advanced through the system.

It is within this context of many regional sensibilities that the Project-Based Learning initiative in Maths and Language has found its way in the government schools of Nagaland.

Thejasino Peseye: Weaving fractions into Naga Shawls

It is clear that initiatives that have found relevance in the mainstream education sector and syllabi will fail if simply ‘cut and pasted’ into Nagaland unless the community is taken into confidence in framing how classes are taught and students learn.

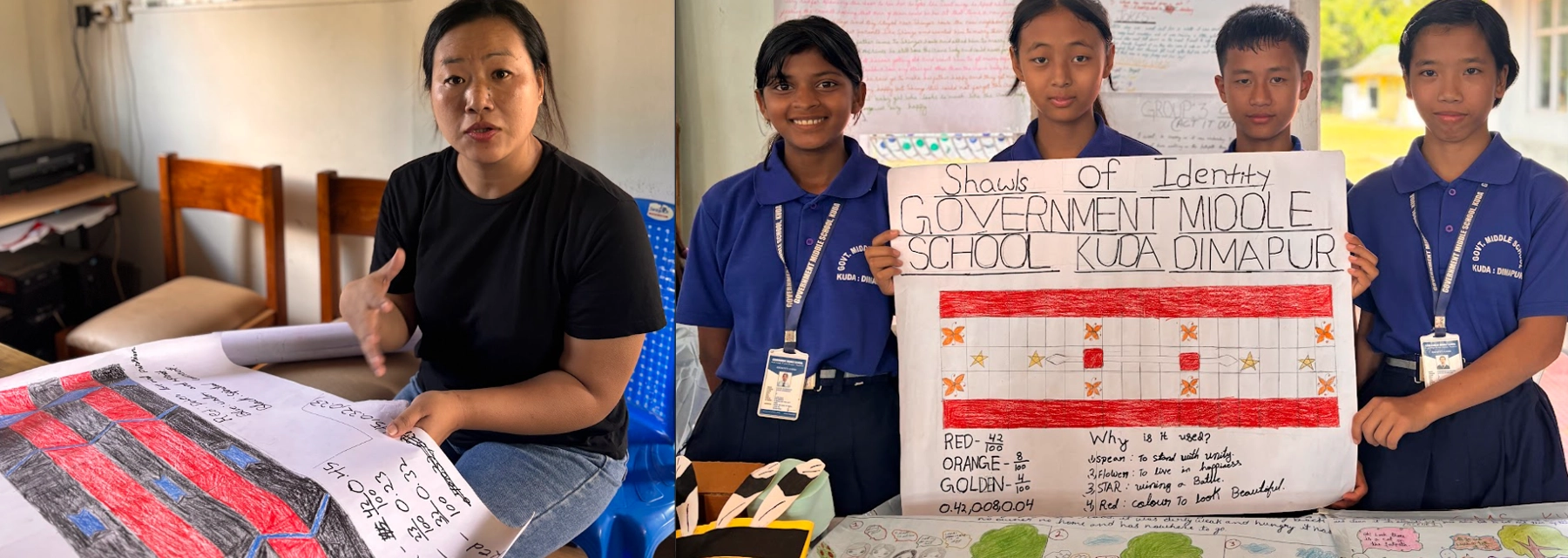

When we met Thejasino Peseye, a math teacher at Government Middle School, Kuda Dimapur, she repeated this concern. Thejasino, with a decade of teaching experience, remains the only math teacher for Grades 5 to 8. Her classroom brings together students from diverse communities across Dimapur, each shaped by different social and cultural contexts. How, she asks, does one find shared commonalities in such a classroom?

The PBL initiative positions students as active participants in their own learning, guiding them to connect textbook concepts to their communities and cultural traditions. Teachers are now drawing links between students’ different experiences that, until recently, have only existed outside their classrooms.

In her classroom in Dimapur, Thejasino found a way to make fractions simpler for her students by connecting them to something they knew very well – the patterns of a Naga shawl. Holding up a shawl, she would ask, “if the shawl is made up of 100 squares, how many squares would the shapes of stars and the spear take?” The numbers on the chalkboard transform into shapes and colors familiar to the students, turning fractions into something they can see and touch.

By the end of her lesson, Thejasino would call out fractions – one-half, one-third, one-eighth of the shawl – and her students would convert these calculations into Naga Shawl designs drawn with crayons and pencils.

For too long, education in Nagaland has mirrored models and curricula designed far from its hills and communities. Such approaches, rooted in mainland assumptions of what development looks like, have often overlooked local histories and knowledge systems. When education becomes something to be “delivered” rather than built with the community, it risks erasing the very identities it seeks to uplift. Teachers like Thejasino, who bring Naga identity into the classroom, remind us that development can be imagined through the community’s own lens, not imposed upon it.

Mhonyani Ezung: Kick fighting equations

In Thahekhu Village, Mhonyani Ezung’s classroom often begins outdoors, where her students play games like Gaah Tarimei (seed flicking), Apukhu Kiti (kick fighting) and Aqhedu Kumgho (bamboo pole climbing).

Apukhu Kiti, originating from the Sümi community, is played inside a ring drawn on the ground, where players can strike or block only with the soles of their feet. A match is lost if a player touches the ground with a hand or knee, or steps outside the circle.

As her students navigate the Apukhu Kiti ring, Mhonyani ensures they also calculate the area, circumference, and angles at which the game is played, connecting abstract formulas to the knowledge they use in daily life. Mhonyani’s approach to project-based learning shows that a heterogeneous mix of experiences that her students have grown up with, can be integrated into learning. On a piece of paper, she shows us a list of games, some that are favourite picks of her students, that she used to teach length, breadth, area and perimeter.

At the PBL fair, we met teachers like Mhonyani, actively working to bring Naga indigenous knowledge and perspectives to project-based learning – and, crucially, in a way break the common criticisms of PBL. While PBL encourages hands-on learning, it can sometimes assume access to resources, materials, or experiences that tribal students may not have, making lessons feel alien. Mhonyani’s approach, however, bridges the yawning gap between textbooks and lived realities, because it gives teachers the freedom to experiment with how education is delivered.

Project-Based Learning (PBL) as an approach to education in Nagaland responds to pressing educational realities. As per ASER 2024, only 27.1% of Grade 5 children in government schools can read a Grade 2-level text, and just 12.7% can perform division, while NAS 2021 reports state averages of 53% in Language and 35% in Mathematics.

However, the challenge before Nagaland’s education system is not merely about access or measurable outcomes. It is about reclaiming the agency to define what learning means and whose knowledge counts.

In a world where education is prescribed as a cure, PBL gives students the space to explore what matters to them and the world they grew up with.