By Abhishek Jain, Head, Public Policy at Mantra4Change.

Evolution of ‘education policy’ in India

Post India’s independence in 1947, multiple commissions were set up over 2 decades to ideate and design independent and modern India’s educational system. Gradually the central government realised that there was a need to formulate a national level policy to promote and regulate education in the country. Since independence, India has seen 4 key national level policies on education starting from the first one in 1968, next in 1986, then in 1992, and finally the current policy introduced in 2020.

Presently, the governing document for India’s ‘education policy’ is the National Education Policy, 2020 (‘NEP’)1. The NEP aims to sustainably transform India “into an equitable and vibrant knowledge society, by providing high-quality education to all, and thereby making India a global knowledge superpower”2.

Notably, the nomenclature of the NEP also marks an interesting departure from its predecessors in that they were framed as national policies on education as opposed to ‘education policies’. The shift to ‘education policy’ reflects a broader evolution in India’s educational discourse—from a centrally administered policy instrument to a much-needed modern, holistic and decentralised approach to ‘education policy’ in the 21st century.

Understanding India’s Education Policy Landscape

A. Scoping India’s education policy

It is imperative to note that while the NEP is considered as one of the key instruments of India’s current education policy, it is by no means the only piece. Education policy refers to the underlying framework and discourse that shape education at all levels, from early childhood to higher education and today even lifelong learning. In India, this dynamic set includes the Constitution, statutory laws and policies passed both at the central and state level, strategy documentations for education delivery created by stakeholders, policies of private educational institutions etc.

India’s education policy starts first with the law of the land, i.e., the Constitution of India which became effective from January 26, 1950 (‘Constitution’). While there are many provisions that directly or indirectly pertain to education, importantly, the Constitution recognises the right to free and compulsory education to all children of the age of 6-14 years as a fundamental right3, and further places a positive obligation4 on the state to make effective provisions for securing the right to education5. It is in furtherance of the law of the land (i.e. the Constitution in the Indian context), and the mandate to guarantee the right to education (both directly and indirectly) that the central and state governments have ideated and implemented countless laws and policies that determine who gets to learn, what they learn, from whom they learn, and how the learning translates into value (i.e., opportunities that ultimately shape an individual’s life).

B. Ownership of India’s ‘education policy’

Typically ‘education’ is a subject over which the state retains ownership of law and policy making. India is no exception, where the state i.e., the government retains ownership and control of the ‘education policy’ space. Interestingly, in India, since ‘education’ as a subject falls under the concurrent list6 i.e., it is a subject both the Parliament (central level) and the Legislature of any State (state level) have the power to make laws and policies on7.

This shared responsibility leads to scope for innovation since in education a ‘one size fits all’ approach is unlikely to work in a diverse demography like India, but at the same time also for challenges in terms of implementation since different states would prioritise different goals and agendas which could at times lead to non-uniform implementation or mis-alignment with the desirable national standard. Consequently, the web of what constitutes ‘education policy’ in India is a very extensive and complex framework.

C. India’s Public Education Delivery Machinery: Policy to Implementation

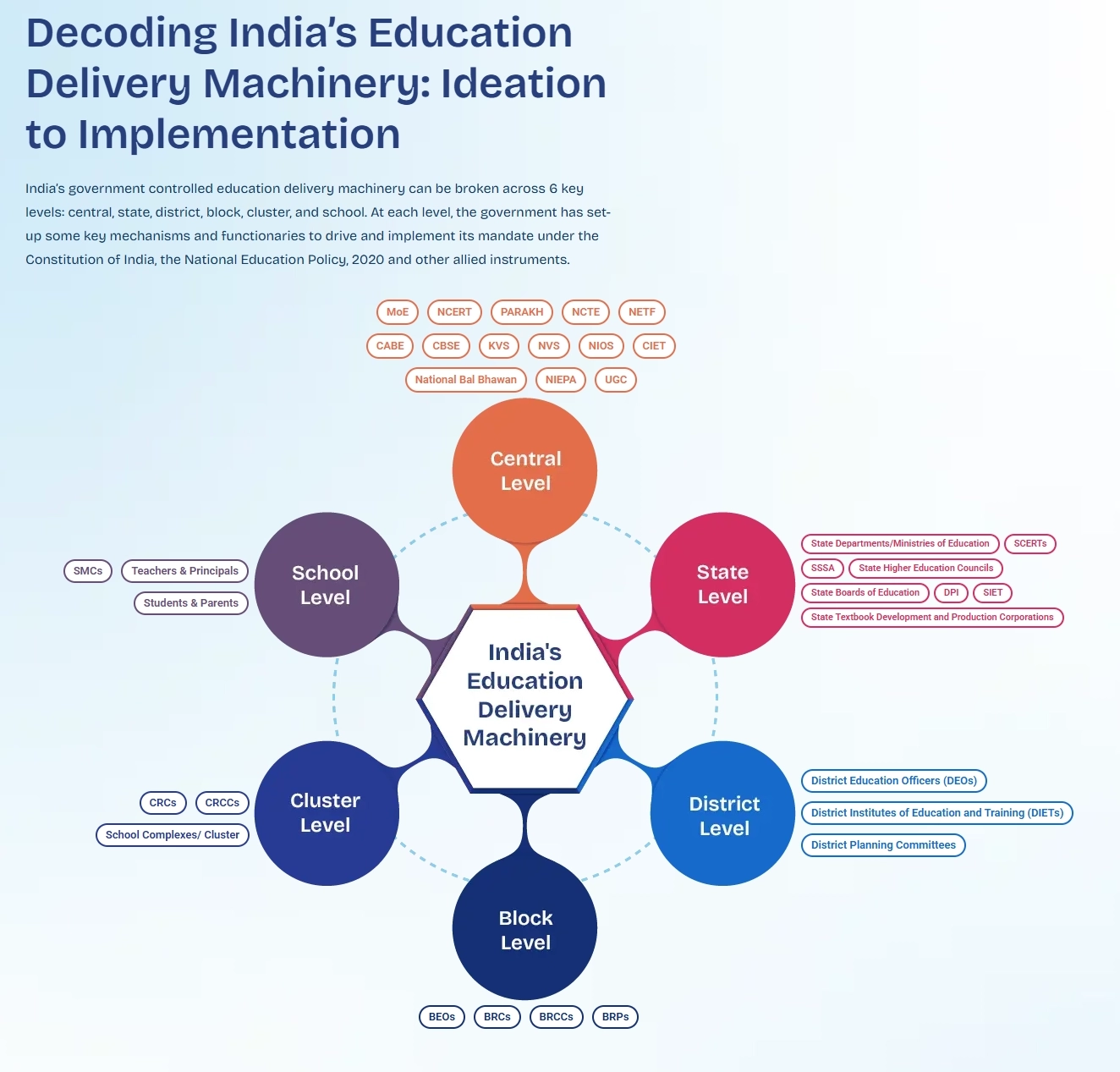

Within the public education space, the policy framework is no less complex, with a diverse array of different public agencies with overlapping roles/functions operating both vertically and horizontally. You can find below a map to understand India’s public education delivery machinery:

India’s education policy ecosystem operates across six interconnected levels, where policy flows both upward (bottom-up) and downward (top-down):

- Central level: instruments such as the Constitution, the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009, NEP, etc.

- State level: instruments such as the Tamil Nadu State Education Policy 2025, the Karnataka State Civil Services (Regulation of Transfer of Teachers) Act, 2020, etc.8

- District level: across approximately 800 districts of India institutions like District Institutes of Education and Training (DIETs) and District Planning Committees play a pivotal role in contextualizing and implementing policy.

- Block and Cluster level: Block Resource Centres and Cluster Resource Centres provide localized support within their jurisdiction and also manage and enable localised policy implementation.

- School level: School Management Committees (SMCs) represent the most direct form of community-led governance, shaping school-level decisions. This level also serves as the most integral level for feeding insights back into the system (bottom-up) given that it directly gets feedback from 2 key stakeholders - teachers and students.

Relevance of global education policy instruments on India’s education policy

India’s Constitution expressly mandates that the state shall “foster respect for international law and treaty obligations in the dealings of organized peoples with one another”9. This implies that the state would be tasked with additionally ensuring compliance with obligations that India has either under international law or by way of any treaties that it has ratified. To take 2 key examples to demonstrate India’s obligations in relation to 2 key instruments that recognise the right to education – firstly, India has signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)10 which though not a legally binding instrument, it reflects India’s commitment to a foundational instrument of international law that sets out fundamental human rights to be universally protected including the right to education11. Secondly, India has also ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966, which imposes a positive obligation12 on the state to take necessary steps to protect and secure the right to education13. Hence, when ideating and evaluating India’s national education policy it is important to construct and understand the same harmoniously with India’s obligations under international law.

Conclusion: Shaping India’s education policy landscape

Like most policy domains, India’s education landscape is shaped by a diverse set of stakeholders operating across multiple levels. Reform in such a system cannot be unidirectional. Driving progressive, system-level reform requires a dual approach top-down and bottom-up. At the central and state levels, the role is primarily that of enablers and drivers: setting vision, allocating resources, and creating legal and policy frameworks that guide the system. At the district, block, cluster, and school level, however, there is a need for the system actors to recognise and fulfill the dual role as the machinery responsible for implementing the policy and also as decision makers on the direction and evolution of these/new policies.

The future of India’s education policy depends on how effectively stakeholders will interact across levels both top-down and bottom-up.

* By Abhishek Jain, Head, Public Policy at Mantra4Change.

* AI Use Declaration: Assistance of AI tools was taken for analysis and copy-editing of this blog.

1 The National Education Policy 2020 (‘NEP) was approved on July 29, 2020 and is accessible here.

2 Page 6 of the NEP.

3 Article 21A of the Constitution.

4 A ‘positive obligation’ put simply is an obligation to take action, or an obligation that places a duty to act on a party.

5 Article 41 of the Constitution.

6 List III – Concurrent List of Schedule VII of the Constitution

7 Article 246 of the Constitution

8 As discussed in the previous section, ‘education’ falls within the concurrent list and as such both the central and state governments can pass laws and policies on the same.

9 Article 51 of the Constitution.

10 The UDHR was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948 (General Assembly resolution 217 A)

11 Article 26 of the UDHR.

12 Article 2(1) read with 13(1) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966

13 Article 13 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966